|

| Milwaukee Sentinel 11.21.1969 |

Source: "Mrs. Paradowski Dies, 55," Milwaukee Sentinel, November 21, 1969, pg. 13

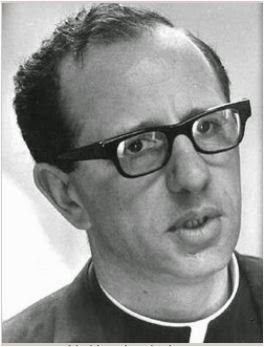

The other individual who deserves special mention comes from an Italian family but he married into the Paradowski clan. His name is probably familiar to anyone who lived in Milwaukee in the late 1960's: James Groppi. He was another individual who set an example by his actions, although many of us did not see it at the time.

Father James Groppi started his career as a regular parish priest at St. Veronica's parish in 1959. (I was actually attending church there at that time, but I was way too young to remember him). In 1963, he was transferred to St. Boniface, an inner-city parish. It was there that he saw first hand the detrimental affects of poverty and social injustice. He decided he must do what he could to correct the situation.

It is way beyond the scope of this note to try to tell the story of his work. (Those interested can read the sources listed below, and many others, that can be found about his career.) Suffice it to say that his activities garnered national attention, and quite a lot of local animosity. Much of that animosity arose from the historically Polish neighborhoods on the South and East Sides. One of the things that Father Groppi strove for was the basic principal that anyone should be able to live in the neighborhood of their choosing. However, that's not the way many in the Polish neighborhoods saw it. By the 1960's, those neighborhoods were already loosing much of their ethnic identity and cohesiveness as young families choose to move to the suburbs. This flight meant there was room for non-Poles to move in, but many in those neighborhoods wanted to shut out any non-whites. The perceived differences of the new-comers generated fear: fear of increasing crime and decreasing property values, among others. As a leader of the civil rights movement, and one who kept pushing, and pushing and pushing even harder for fair housing, Father Groppi became a lightning rod for this fear and the hatred it generated.

There was one especially regrettable incident in August, 1967. In what was undoubtedly intended as a provocation, Groppi held a picnic for 250 of his mostly-black parishioners in Kosciusko Park. An angry crowd of 2,000 whites gathered and jeered at them for the audacity of coming into "their" neighborhood. The mob threw rocks and bottles at the picnickers. Police wearing riot gear had to come to restore order. It was not one of the bright spots in the history of our community. Now, we recognize that James Groppi was right, and those who opposed him were wrong. A person should not be denied a house because of the color of his or her skin. It was sad to see the once vibrant, close-knit Polish neighborhoods decline, but that was caused by many socio-economic factors and not by the individuals who wanted to move into the community.

Without trying to downplay the error of our community, it is also safe to say that the prejudices of the Polish community were probably shared by most of the whites in Milwaukee at the time. If our reactions to Father Groppi were more violent than others, it may be because it was our neighborhoods that were most "on the front line." Father Groppi was definitely ahead of his time in his views on civil rights and it was our fault not to recognize more quickly the justice in his actions.

Another belief held by Father Groppi that was not shared by most at the time (and which is still anathema to many, including the Church hierarchy) was the conviction that Roman Catholic priests should be allowed to marry. James Groppi carried out that conviction in April, 1976, when he married the woman he loved, Margaret Rozga. (She is the daughter of Jeanette (Paradowski) Rozga, and a first cousin, 2x removed to Roman J. Paradowski (Featured Profile #39)). The two had met during a voting rights trip to Alabama in 1965 which only goes to show that the Milwaukee Polish community also had civil rights advocates. The marriage meant that he could no longer function as a Roman Catholic priest. He thought briefly of converting to the Episcopal faith and the Episcopal Bishop in Detroit offered him a position. However, Groppi could neither give up his Roman Catholic faith, nor live apart from his city. Instead, he returned Milwaukee and drove a cab.

He died in 1985 at the age of 54 from a brain tumor. He left his wife and three children surviving. His funeral mass was said in St. Leo's Church and he is buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Sources:

Balousek, Marv, "James Groppi: Radical Priest and Unpopular Hero," in Wisconsin Heroes, excerpted at Madison.com

Folkart, Burt A., "James Groppi, Ex-Priest, Civil Rights Activist, Dies," L.A. Times, November 5, 1985

Fr. James Edmund Groppi at Find a Grave.

Gurda, John, The Making of Milwaukee, Milwaukee County Historical Society (1999, 2006, 2008)pgs. 365-76.

Heise, Kenan "Milwaukee Activist James Groppi, 54" Chicago Tribune, November 5, 1985

Ivey, Mike, "Father Groppi's Legacy Demanded Stinging Speech, says Rozga," from The Capital Times

"James E. Groppi, Dead at 54; Ex-Priest Led Rights Fight," New York Times, November 5, 1985

James Groppi on Wikipedia

Stotts, Stuart, Father Groppi: Marching for Civil Rights, State Historical Society of Wisconsin, 2013